Beethoven’s Mass In C

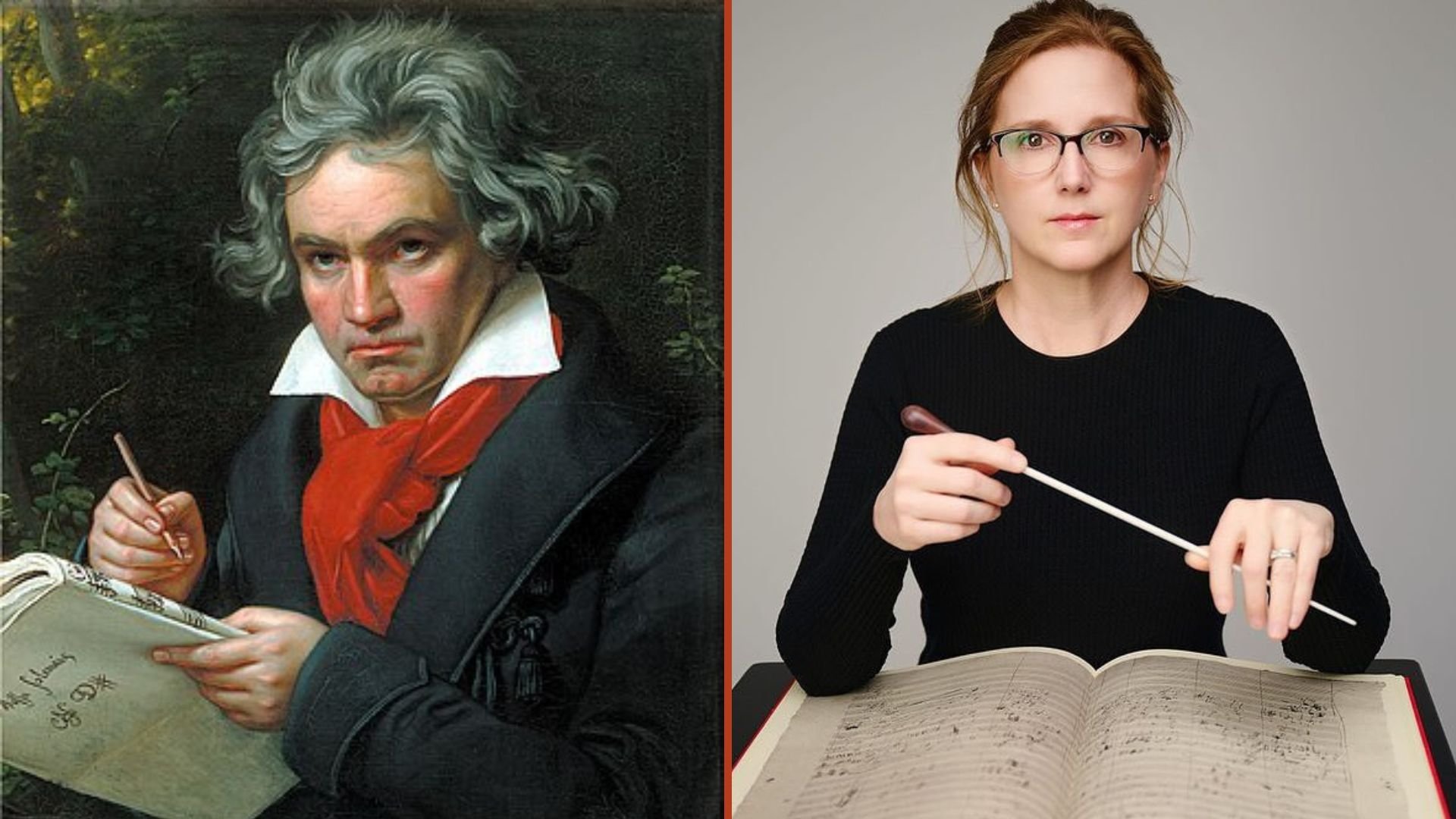

by Erin Freeman

Ludwig van Beethoven (left) and Erin Freeman (right), each pictured with the score of Missa Solemnis

What an honor it is to present Beethoven’s Mass in C Major with the City Choir of Washington on June 1! While not the most famous of Beethoven’s choral works (that would, of course, be the ninth symphony), and certainly not the most terrifying (the Missa Solemnis), this early work points to Beethoven’s personality, ethos, and musical style just as easily as those two iconic works. While ostensibly simpler and less adventurous, the Mass in C has everything these two works have: a creative and adventurous approach to form and ‘rules,’ dramatic drama (yes, even his drama is dramatic), fugues (because who doesn’t love a fugue?), and a belief in the potential for mankind to band together and change the world.

Creative and Adventurous Approach to Form and Rules

Beethoven’s compositional character is at its most authentic when he is breaking the rules. He, for example, added chorus to a symphony (Symphony No. 9); he put a storm in an orchestral work (“Pastoral” Symphony); and he placed a violin concerto smack in the middle of a choral work (Missa Solemnis). In the Mass in C, one of my favorite acts of rebellion is the opening of the Credo. Traditional Catholic liturgy would require that the priest intone the first line of the creed: “Credo In unum Deum” (“I believe in one God”), only allowing the congregation to join in on “Patrem omnipotentem” (“the Father all-powerful”). Additionally, the word “Credo” should only be heard once. In Beethoven’s Mass in C, however, the chorus (representing a congregation of sorts) actually gets to sing the first line, and, on top of that, they repeat the word “Credo”—four times! Each time they sing Credo, the excitement builds, until it explodes in ecstatic jubilation. This is truly a mass for the people to sing—not relegated to the authorities. Oh, Beethoven—such a rebel!

Dramatic Drama

I know—that’s redundant, but Beethoven’s music certainly warrants such repetition with its swift tempo changes, huge leaps, characterful text setting, and dynamic contrasts that will knock your socks off. In the opening 64 measures of the Gloria, for example, he changes dynamics eight times, resulting in a sonic change of direction roughly every ten seconds. On top of that, the chorus has several vocal leaps of an octave or more. One of the most effective of these turns of phrases is his setting of “Adoramus te” (“we adore you”), which is low, piano, hushed, and reverent, followed immediately by “Glorificamus te” (“we glorify thee”), which is high, fortissimo, and bright, and only gets higher and brighter as the phrase is repeated (counter to liturgical practice) three times! Later in the same movement, the music turns operatic as the mezzo soloist, followed by the rest of the quartet, introduces the text “Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis” (“He who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.”). Accompanied by a darkly pulsing orchestra, the chorus, as if playing the roles of a congregation of sinners standing around four lead characters on a darkly lit stage, repeats the “Miserere Nobis,” first piano and then immediately forte, desperately and theatrically calling out for forgiveness.

Fugues

We generally associate fugues with the Baroque-era master, Johann Sebastian Bach. After all, Bach did solidify the form—a kind of canon (or round) with strict rules. He was able to take this formal structure to sublime heights, enrapturing the listener in a swirl of expression and emotion. Since Bach’s time, composers have sought to demonstrate their compositional prowess by inserting fugues into their compositions. Mozart, Haydn, and Martines all successfully composed fugues as part of their choral works, symphonies, and string quartets, as did Beethoven. Beethoven’s most complex and sublime examples are in his later works—think his ninth symphony, his final string quartets, and, of course, the seemingly unending Missa Solemnis fugues. In his early works, such as the Mass in C, he is just getting his fugal feet wet, so to speak, but he does so with aplomb. He follows the formal traditions set forth by his predecessors, inserting fugues at the end of the Gloria, the end of the Credo, and the Osanna. While these are generally modest representations of his contrapuntal genius, there are a few Beethoven markers throughout—little jabs at tradition or creative twists. For example, in the finale of the Credo movement, he toggles between full chorus and solo quartet, mixing up the dynamic texture, he lands on an unexpected fermata (or hold) in the middle, and, just when you think the natural flow of the fugue has returned, he interrupts the line with huge, dramatic shouts of “Amen!” Or, in the Gloria finale, he twice interrupts the traditional “Cum Sancto Fugue,” which follows all the rules à la Bach, with references to the music of a previous section—weaving the two together with the maturity of a much more seasoned composer.

Brotherhood of Man

When Beethoven set the text of Friedrich Schiller’s poem “Ode to Joy” in his ninth symphony, he was solidifying his strong belief in the power of the brotherhood of man. “Brotherhood unites all men where your gentle wing's spread wide.” This theme of unity and the empowerment of the individual was not new by the time it appeared in his last symphony, however. He touched on the topic in his 1808 Choral Fantasy, and he famously changed the dedicatee of his third symphony from Napoleon to a more generic “Hero” after the French general named himself Emperor, a move Beethoven believed border on tyrannical. In the Mass in C, written in 1807, he musically shares his thoughts on war, mercy, forgiveness, and the power of humanity. For example, in the final movement, in typical Beethoven style, he messes with the traditional structure of the liturgy, reordering the text to make a personal statement. The text as prescribed is as follows:

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the word, have mercy on us.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the word, have mercy on us.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona nobis pacem.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the word, grant us peace.

In the first half of the final movement, Beethoven generally abides by tradition. The music begins with drama and angst, and then resolves to a peaceful and stable C Major when the text turns to the subject of peace. Soon, however, Beethoven brings back the Agnus dei and miserere text, with its requisite fear and foreboding. It’s as if Beethoven is reminding us that war and conflict can reappear at any time if we become too complacent. After this martial interlude, the text does return to the Dona Nobis Pacem, but this time, the music directly quotes the first movement of the mass. This clever turn of phrase reminds us of the opening text: “Kyrie eleison” (“Lord have mercy”), adding some individual responsibility to the search for a more peaceful and just world.

In Conclusion

I opened this essay stating how honored I am to present this work with the City Choir of Washington. As a bit of background, I wrote my dissertation on Beethoven’s later mass, the epic Missa Solemnis, and I’ve conducted his ninth symphony and prepared it multiple times. To travel back to a younger Beethoven and discover the clues that would lead to his later masterpieces has been a joy. It reminds me that we must continue to nurture and support new ideas, young voices, and those who are willing to take chances. If we don’t, we might miss out on the next iteration of the “Ode to Joy.”

Come hear the City Choir of Washington perform Beethoven’s Mass in C Major on June 1st!